You’ve known for some time that a certain employee and his boss aren’t getting along. You have valuable advice for both parties, but hoped they could work out their differences before intervention was necessary. One day you hear the two arguing behind closed doors and realize then that you must step in and resolve the conflict. You manage to stop them from arguing and disturbing the workplace, but can you repair the relationship and how?

Employer-employee conflicts present challenges for HR leaders. Supervisors and subordinates don’t always know what to expect from each other. And when communication breaks down, the chances for resolution are seriously impaired, often making a separation necessary. An unlikable boss is one of the top five reasons employees leave their jobs.

Key Takeaways: When HR Steps In or Out of a Boss & Employee Conflict

- HR should intervene when conduct crosses the line: HR needs to step in if workplace behavior violates policy, disrupts the work environment or shows a persistent power imbalance that can’t be resolved informally.

- Understand power dynamics and perception: Manager-employee conflicts are complicated by inherent power imbalances and perceptions of HR bias, so fair, neutral handling and clear communication are essential.

- Use structured conflict resolution: Establish a formal conflict resolution or mediation program (with in-house or outside mediators) to guide parties toward understanding and lasting behavioral change.

The Power Imbalance in a Boss-Employee Conflict

The nature of the supervisor-subordinate relationship is an imbalance in power. Power is about what people need and their options for getting those needs met. A boss, for example, needs workers to perform their jobs effectively. Employees need their boss’s approval of and recognition for a job well done. When both camps know each other’s needs, they can respond to each other with mutual understanding and respect.

However, when the power imbalance stops functioning — regardless of the cause — both parties can become defensive and resolute in maintaining their positions.

The age-old “management vs. worker” battle cry hinders HR leaders’ ability to resolve workplace conflicts. The employee might see HR and the boss as allies and therefore part of the problem rather than the solution. Bosses might think HR is “on their side” because both are members of the management team.

A Conflict Resolution Plan

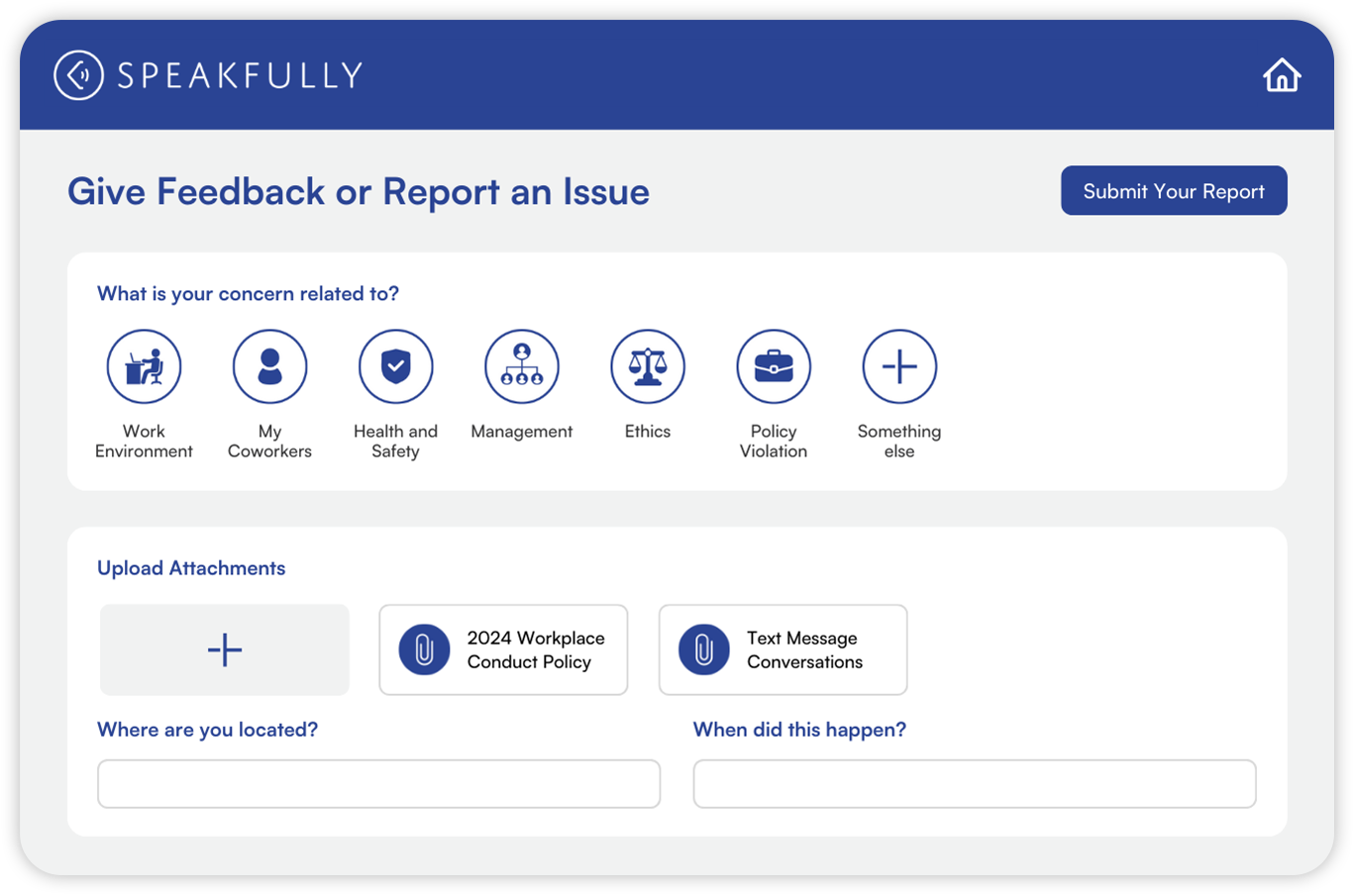

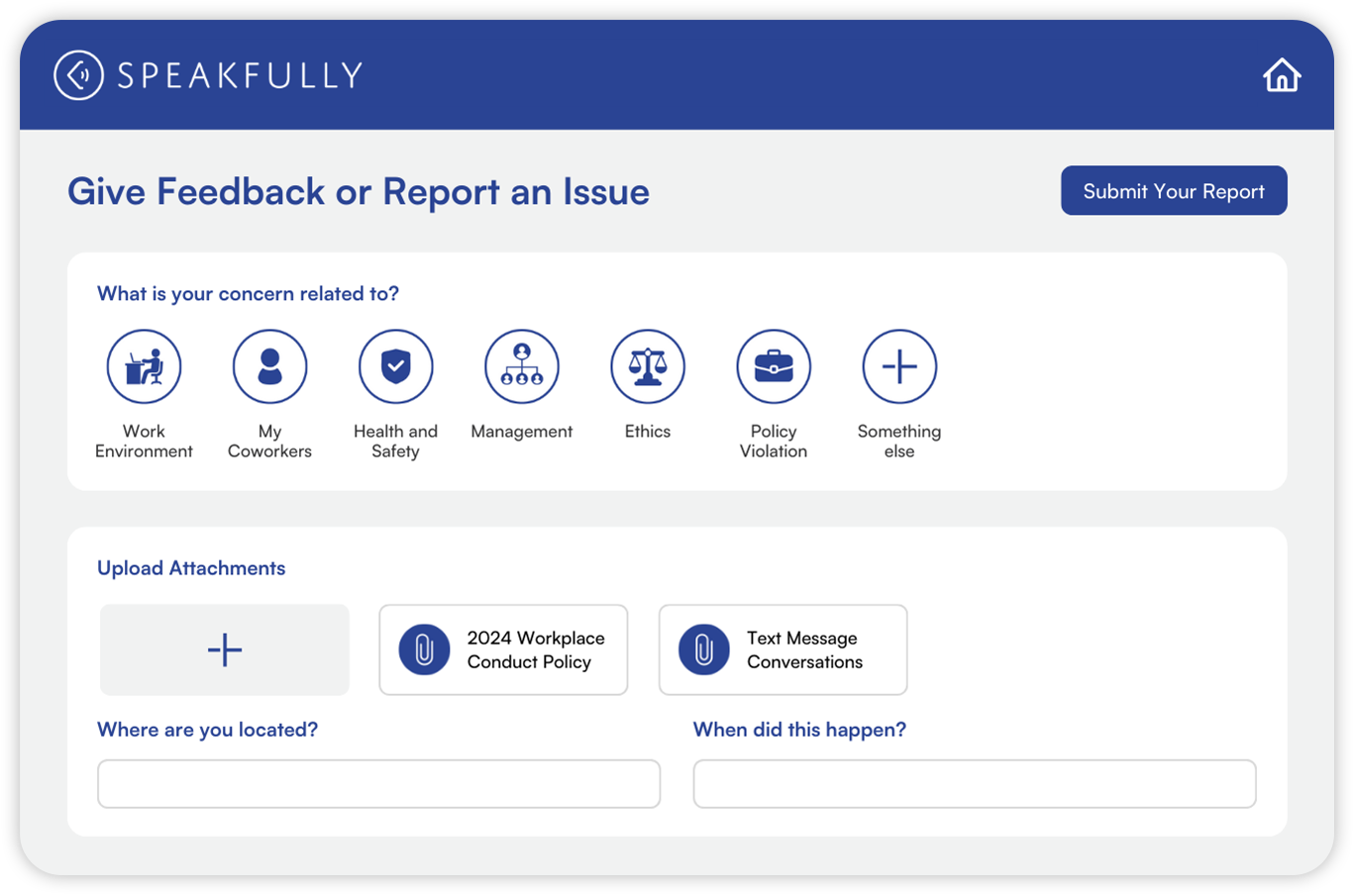

HR must get involved in employer-employee conflicts when behavior violates the company’s policy on workplace conduct. But to avoid the appearance of favoring one party over the other, you might consider setting up a conflict resolution program. Mediators in the program help the parties move from conflict to resolution and oversee the process. On paper, the program should describe employees’ mediation rights and resolution options. For example, a provision might include the employee’s right to include a third-party in mediation sessions.

Conflict resolution programs can be introduced to staff in onboarding sessions or a wellness program as an emotional well-being component. When new hires learn about the program, they’re more likely to think of workplace conflicts as risk-free situations that can be amicably resolved rather than opportunities for being double-teamed by management.

HR as the Mediator

A mediator’s ultimate goal is to get the parties to change how they interact with one another. HR leaders often act as in-house mediators, since they usually know the parties. But familiarity can be either an advantage or a hindrance. Mediation requires an objective view of each party’s personality, work style, habits, expressions and other traits. A biased opinion defeats the purpose of mediation.

An experienced mediator wants to:

- Get the parties to stop thinking about past arguments, slights, disagreements and other negative behaviors as a first step toward encouraging more positive thinking.

- Find out what each party wants out of mediation and ask each one separately.

- Be realistic about the outcome and don’t look for overnight behavioral changes.

- Encourage the parties to continue the process long after the mediator’s direct involvement ends. The mediator’s role is to keep the parties talking and listening to each other.

A Third-Party Mediator

If being an objective mediator is too big a challenge, bring in an outside mediator. Select one that:

- Has workplace dispute experience.

- Knows about basic employment laws.

- Charges reasonable fees.

- Shares references from current or past clients.

For a national directory of dispute resolution organizations, visit the Society of Professionals in Dispute Resolution’s website.